I.

Once, in Maiduguri, I visited a photo studio. It was 2016 and Boko Haram had eaten deep into the city. Buildings were half blown up, charred, taken over by the military. Streets were deserted and under close watch by the Civilian Joint Task Force. The owner of the studio—a young man in his 30s—had come from Jos about 7 years earlier. His studio was open, always, even during the most intense days of the bomb blasts. Customers would pack their fancy clothes, brave the wildness of the city and come into the studio to be photographed. On some days when a bomb went off during the photoshoots, he and his customers would lie face down on the floor of the studio while the city melted under gunfire.

We were talking about his days in Jos before he came to Maiduguri. Days of “innocent sun”, he called them. He had moved further north because he wanted to photograph the beauty of the city and its Islam.

—The first time I made a portrait of someone here I thought to myself: all of Allah’s handwork is beautiful.

He still remembers the first portrait he made in Maiduguri: a petite, smiling woman who had switched from her hijab to a flowing dress, jeans and heavy makeup. A small red dot at the center of her forehead. There was a large version of the portrait on his studio wall. He regarded it like a scar from battle, an enduring spoil of war. Then he showed me a stack of photographs.

—Look at these. The owners of these photographs never returned to collect them. In another time I would have assumed they simply aren’t interested in getting the pictures they paid for. But in our situation, you have to consider the possibility that the reason they haven’t come to collect their pictures is because they might actually be dead.

I asked him what he thought could be the reason people in the middle of terror attacks would want to make portraits of themselves in a photo studio.

—That is the thing about unchecked, radical, pervasive violence. Nothing that happens within it makes any sense. I imagine the people wanted to be able to do something normal, wanted to be able to imagine some other reality. They wanted to be able to cope.

—And how about you? I asked. How did you cope?

He sat, closed his eyes and rested his head on a wall. He opened his mouth to speak but instead he broke into a song.

II.

It is now 10 years of Boko Haram. Certain names and events have become incisions on the collective conscience of Nigerians: Shekau. Bama. Baga. Gwoza. Maiduguri. Potiskum. Gamboru. The boys in school at Buni Yadi, lined up and shot in the head. The girls in Chibok. The girls in Dapchi. Hauwa Mohammed Liman, 24, a mid-wife working with the International Committee of the Red Cross, executed publicly by Boko Haram. 15-year old Leah Sharibu, still held captive by Boko Haram. Names and events that should be cane-strokes but are now motifs of the Nigerian landscape.

III.

Every photograph of mass violence looks the same: burning vehicles and houses, smoke, scorched earth, scattered brick, disappearing skies, people wailing, people running, streets littered with bodies. How does one discuss these images we have now become acquainted with—of mass deaths, bodies bludgeoned, torn-apart, burnt, ravaged, ripped open?

To be Nigerian is to pretend to be unaware, to trudge on in a stasis. One can argue for this practiced forgetfulness, for how it is the Nigerian way of escapism. Truly, a consistent barrage of violent, sad news bears on the mind, and for the helpless, learned apathy is perhaps the only form of self-defense. But apathy engenders silence and silence in the face of mass violence to others can be construed to signify acquiescence.

IV.

I suppose that it is impossible to write about violence with precision, and any critic attempting this task must proceed from a place of failure. This failure has nothing to do with the critic or the subject of his criticism but is rather a consequence of language’s misfortune. Language is unfortunate. As the equipment of criticism, the responsibilities demanded from language make it difficult for it to be of any use. Violence and language are antithetical.

Words are, of course, usually spoken within violence by the violent. And in this regard Mary Louise Pratt’s argument1 that violence is always accompanied by language might be correct. But the kind of language that Pratt talks about is in itself another tool of violence; it lies solely within the grasp of the violent for the purpose of violence. The victims of violence have no share in the language that perpetuates it—this is the kind of language that acts upon them and not for them. Shekau, for example, has more words recorded around his actions since 2009 than his victims, and now that I think of it, perhaps than by Nigerians as a whole. He has warned, threatened, promised, cursed and prayed. What have his victims said in response? What have Nigerians said collectively in response?

The language violence wants to stop is metaphysical, it transcends the ability to speak literal words. I am talking about language as a compass for navigating the world. This is the kind of language violence robs us of.

Yet, unfortunately, it is to language that the critic must return. He must put it to work, beat it to shape, stretch it to its limits—this equipment with which we navigate the world. And what kind of language can navigate through, out of, and perhaps, combat violence?

V.

Every story of violence is a black, sad song from which no rationale can emerge. It seems easy to understand the sadness of violence but the blackness of violence might require elucidation. Victims of violence know this blackness in immeasurable entities: Pain, shock, trauma, loss. The latitudes of these are immeasurable—they exist together as an endless sphere of blackness in the psyche.

But how about us, onlookers from outside this violence? I propose that the blackness surrounding us is manifest as silence. Unlike the blackness that surrounds victims of violence, the blackness surrounding onlookers of violence is measurable. We know for instance the amount of outrage in response to the first news of Boko Haram’s bombing. We know the amount of outrage one month after, one year after and now one decade after. We recognize as it dwindles, as news of this kind—news of mass deaths—take the backstage.

VI.

Why is there a manifest silence among us who look at violence from the outside? It is certainly not because we do not care. It is also not because we are not appalled. Rather, we are silent because we do not want to imagine. Imagination requires the creation of some mental image, some world where another reality can come alive or where the present reality can continue. This is why we do not want to imagine or why for us violence remains unimaginable. We do not want to participate in violence, we do not want an image of violence in our minds, we do not want violence in our alternate reality and we definitely do not want it in our present reality. Yet, violence is continuous and the violent never relent in their violence.

VII.

Silence offers no resistance, only capitulation. If the violent can imagine violence then violence is not unimaginable. It is therefore inside this realm of imagination that our work lies: we must step inside the blackness of violence to offer the language of resistance. This is why a photo studio that makes portraits in the middle of bombings is important: it is an unimaginable imagination, that in the middle of such dastardly acts the people of Maiduguri can dare to imagine a world where bombs are not going off, where the only shots in the city are those in a studio, from a camera. This is why Fati Abubukar’s work3 in Borno is important, that she can imagine the possibility of documenting the culture of a people literally in war time. This is why Rahima Gambo’s work4 in the North is important, that she can imagine schoolgirls playing a regular classroom game in the same region where Boko Haram has kidnapped hundreds of schoolgirls.

VIII.

Violence and language are antithetical but only if we surrender to the blackness of violence. The only language that can combat violence is the language of resistance, born out of an unimaginable imagination. In response to violence, we must imagine a world beyond the grasp of the violent and we must imagine it into being.

Footnotes

- Pratt, Mary Louise. “Violence and Language.” SocialText Online. https://socialtextjournal.org/periscope_article/violence_and_language_-_mary_louise_pratt/ (accessed 22 Feb 2019)

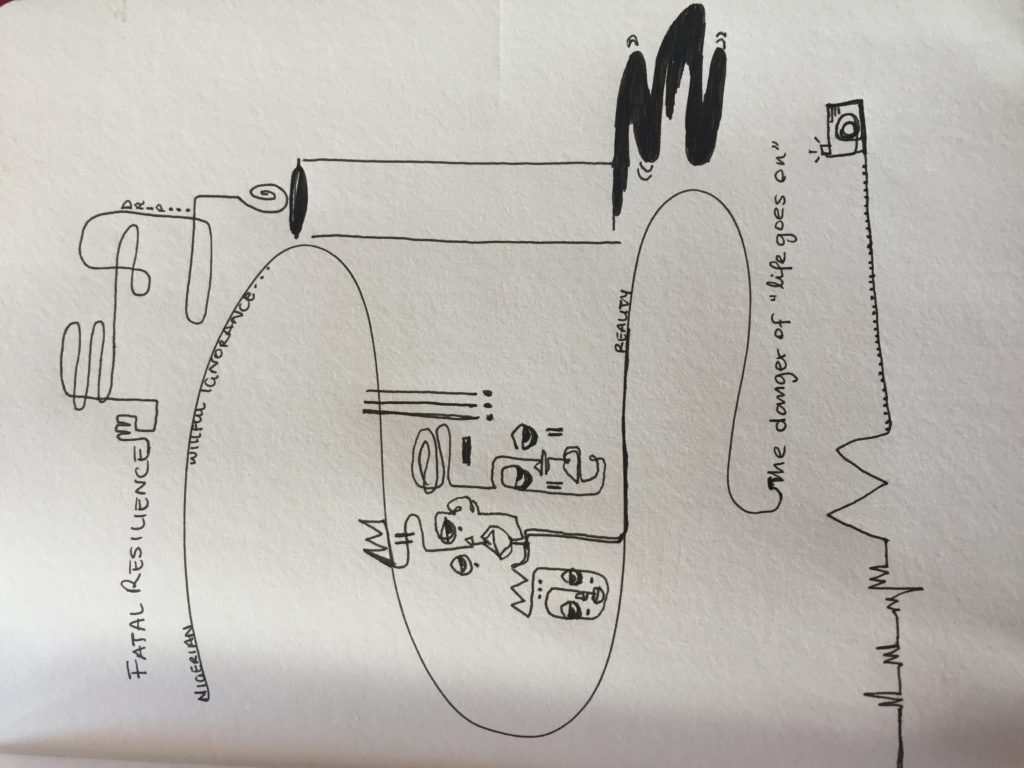

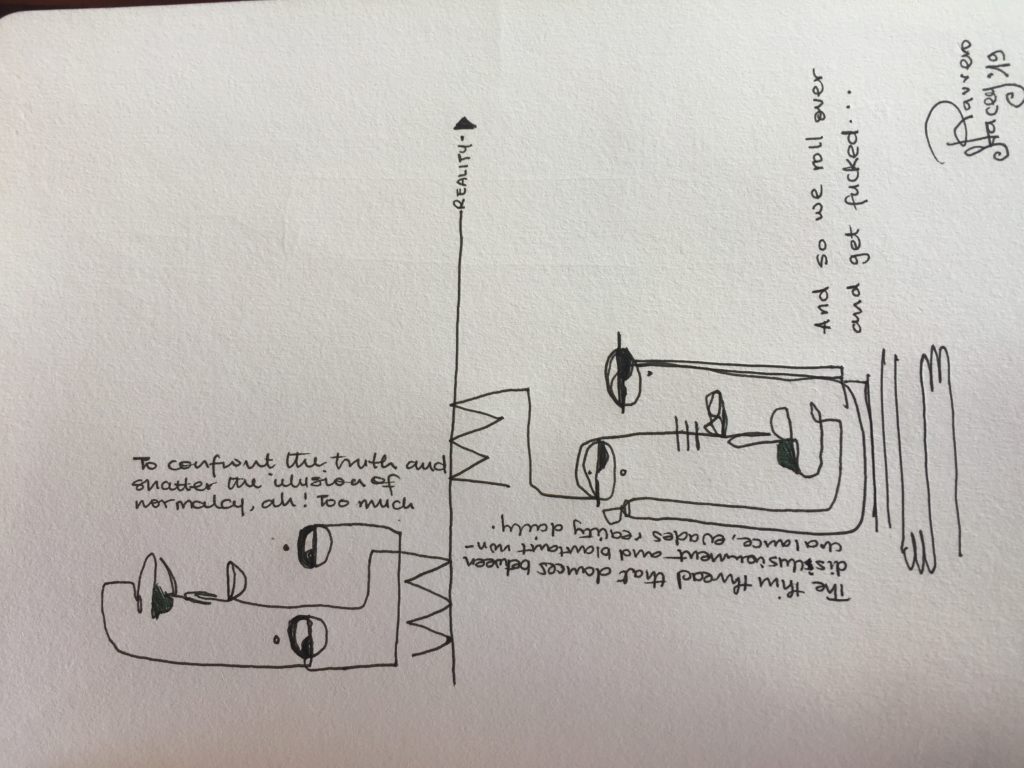

- Many thanks to Stacey Okparavero for agreeing to send in sketches of what came to her mind when she thought of violence in response to this essay and for reading earlier versions of it.

- Abubakar, Fati. “Bits of Borno—Eid Fashion.” Bits of Borno. https://www.bitsofborno.com/#/schwane/ (accessed 22 Feb 2019)

- Gambo, Rahima. “Rahima Gambo | Tatsuniya.” Rahima Gambo. http://www.rahimagambo.com/tatsuniya (accessed 22 Feb 2019)