My dear Alheri, let us sit together at this table, you and I. Do you remember the first time we met? It was in Uyo, at the NYSC1 Camp—everyone from everywhere in the country, poured together into the same pot. It was inevitable: you, boisterous, a full Northern woman and I, curious, a man from the South. Oh, those heady days. All of us in our white shirts and shorts, prancing around under the watchful eyes of soldiers, hormones burning with thoughts of undetected trysts, blood hot from daily parades, sweating in the sun.

I was sad in those days, sullen even. It seemed to me like I was about to piss away one year of my life. Then one day, after we had sweated on the parade ground, you dragged me towards a photobooth.

“Senior man! Cheer up and let us document these moments,” you said, laughing your high-pitched laugh. Years later, in New York, when I read Anne Carson’s The Gender of Sound, I raised my cup in memory of your laughter. That day at the photobooth, I refused to be photographed. You went in front of the camera alone, striking different poses, your laughter reverberating with shutter sounds. I still have photographs of you from those days. Yet, when I think of you, the image that comes to mind is different.

Four schoolgirls in checkered hijabs are standing together. Behind them, a black surface with folds—perhaps a curtain. Consider the shadows in the creases on their hijabs; are they standing in front of a tree? The checkered hijabs are not the only surfaces with patterns; the whole material surface of the photograph itself has blotches—patches of transparent white with different gradations. A splash of blotch falls directly on the right eye of one of the girls, rendering her almost faceless. Yet behind the blotch, her eyes are present. The girls are all looking into the camera, eyes ripe with intent. The girls! What is it about their eyes that seems so generous, yet inexplicable? Is this layer of blotches on the photograph a dividing line between them and me? Or is it how memory works, so that after a while, what remains when I remember you, dear Alheri, is a fading image with blotches for pattern? Now that I think of it, another day, another time and you could be one of these girls.

✢

My dear Alheri, I confess that you were right: I do not know my country. I still remember our long arguments, sometimes late into the night. You always sat on the floor—you hated chairs and sofas and claimed they were the most unnatural things in the world.

“A man’s place is on a mat, always, with legs crossed!” you declared one night, pulling me off the sofa, into the mat with you.

At the time I’d never set foot in the core north of Nigeria. My assumptions abounded beyond my knowledge. You were always laughing; your patience, larger than my curiosity. I remember my folly—the quick simplification that Northerners weren’t educated. I’d pulled out UNICEF statistics3 : only 53% of children in the north went to school, and in the north-east and north-west the percentage of female children in schools was a meagre 47%.

“You’re right,” you said. “It is indeed sad, but what do you think education means?”

I leaned forward, eager to finally win an argument.

“The dictionary definition! The process of receiving or giving systematic instruction, especially at a school or university.”

“Do you think Quranic education is systemic instruction? Does learning to read and write Arabic count?”

“I suppose it would,” I said.

“There you have it. What you don’t understand, is the uselessness of your idea of education to many people up north. For centuries, before the British ever set foot upon our lands, there was another kind of education. People learned to read and write Arabic—it was mostly the Quran, but it sufficed for the kind of life they lived. You could get by much of the north speaking Hausa or Fulfulde. You could probably trade all the way to Egypt speaking Arabic. We developed a way of writing Hausa in Arabic. Ajami. It looks similar to Arabic but it is different. Do you know that Yoruba itself was once written with this script?”

“No,” I said.

“Well. I studied Linguistics so I know some things. After the British destroyed the northern kingdoms in the 19th century they developed a Latin orthography for Hausa. Can you guess what it was called?”

“What was it called?”

“Boko.”

“Ah!”

You laughed. “Surely you must see now, why the name Boko Haram easily finds sympathizers. What many do not know, is that Boko does not simply refer to Western Education or even book. Read the work of Paul Newman4. Boko was not borrowed from English. It is in fact a native word. And it means fraud, sham, deceit. When western education was introduced, it was considered a fraud, a derailment from Islam. I do not need to tell you how much I hate the evil that is Boko Haram. But I understand, at least, the sheer power in its nomenclature. It caters to a hundred-year-old narrative.”

“So, we are in a battle against history then?”

“That’s a grand way to look at it. Yet it might be the only way. There’s a fundamental cultural lacuna. And until we understand it, we can’t win against Boko Haram, child brides, etc. I’d give my life to see these matters brought to an end, but I cannot afford to think like a westerner. UNICEF money cannot undo centuries of tradition, it cannot replace bruised pride. You are passionate Yinka, but you do not know your country.”

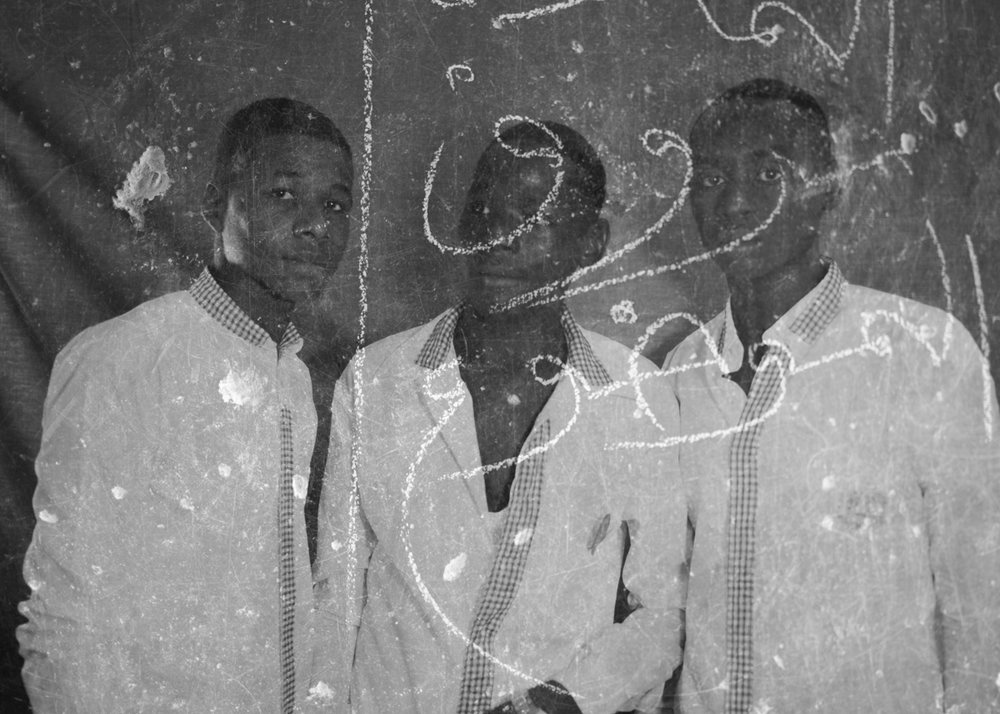

Another photograph, this time, of three schoolboys standing together. Behind them is a similar surface, like the one in the previous photograph. The same folds are present—surely, it has to be a curtain. Their shirts have checkered patterns around the collars and edges. The material surface of the photograph also has similar blotches. And the boy in the center, why is his shirt unbuttoned? He is also the only one in both photographs not looking into the camera. But something else differentiates this image from the first. On the surface are chalk markings in Arabic. One of the lines strikes out the left eye of the boy in the center.

✢

My dear Alheri, do you remember when you lost your engagement ring? You’d always tease me about my nonchalance with issues of marriage. I, in turn, could not fathom how it could be so easy for you to talk about getting married all the time. How were you never afraid of giving yourself over to someone else forever, of bearing children, of starting a family?

When you returned from Kaduna with the ring you rushed to show it to me. That ring, silent and beautiful, worthy of your regal finger. Yet you were sad. The ring had been too loose because somehow, he hadn’t gotten the right size. It kept slipping off. In the end, you wore it only when you had to go out.

“No other man will trouble me now,” you used to say.

That ring, silent and beautiful. We searched everywhere and never found it.

In the days that followed, when we finally admitted that we’d never find the ring, we decided you should tell your fiancé about it.

“I hope he doesn’t get too mad,” I said.

“If he does, my father has a sword! He’s dead meat! Suya ne!”

You saw my face and laughed.

“I was joking!” you said. “Except about the part where my father has a sword. He truly does have a sword.”

“What would he need one for?”

“We live between Southern and Northern Kaduna. You know what that means.”

“You’re speaking of consistent, bloody clashes and mass deaths. Yet you speak as though it were natural, as though life can happen no other way.”

I turned to go.

“Wait,” you said and held my shoulder. “You’re right. I should try not to get used to the possibility of a sudden outbreak of violence daily. What can I do? Move? I cannot live anywhere else. I studied in the UK but I returned to Kaduna. I forced my fiancé to relocate with me to Kaduna. Even here, during this NYSC, I travel every month to Kaduna. I am not like you. I don’t know how to leave.”

One final photograph, my dear Alheri. An open room without a roof. The left and right walls are painted poorly in white. The wall in the center hasn’t been cemented and the lines between each block are still visible, forming a jagged pattern. On the wall in the center is a black patch, probably a chalkboard. It takes up about 40% of the photograph, hanging there like a halo. Around the board are dark patches, remnants of whatever black material was used to darken the board. The floor has weed, stone and sand. Somehow, one gets the feeling that this is a classroom. Was a class ever held here? No matter. Let us meet here, you and I—there are things we must yet learn from each other.

For Alheri (1989 – 2017), a dear friend from long ago.

Footnotes

- National Youth Service Corps—a para-military scheme where all Nigerian graduates serve the country for a year, usually in locations different from where they’re originally from. Established to foster unity among regions in the country after the Civil War in 1973.

- Rukkaya, Hadiza, Falmata, and Rashida are teenage students of Shehu Garbai Secondary School, a government school in Maiduguri, Borno State. Public schools were allowed to re-open after a two-year closure was enforced by the state when over two hundred school girls were abducted by Boko Haram insurgents from the town of Chibok. Maiduguri, Nigeria, 2016.

- UNICEF. “Education | UNICEF Nigeria.” Unicef.org https://www.unicef.org/nigeria/education (accessed 11 March 2019

- Newman, Paul ‘The Etymology of Hausa boko’. Mega-Chad Research Network / Réseau Méga-Tchad (2013)

- Three students from Shehu Sanda Kyarimi government school. During the height of the insurgency it was feared that some students were Boko Haram members. Officials described secondary school students as both victims and perpetrators. Maiduguri, Nigeria, 2016.

- The burnt shell of a classroom at a destroyed school in Bayan Quarters, known as the neighborhood where the Boko Haram ideology began. Maiduguri, Nigeria, 2016

- Much gratitude to the photographer Rahima Gambo (http://rahimagambo.com) for her generosity and permission to use her photographs